CW: Intimate Partner Violence

“I was born a woman. That comes with certain risks,” opines Ami, a single mother of two from Missouri, as she waits for her medical abortion. She, like so many of the women featured in HBO’s Abortion: Stories Women Tell, has driven across the Illinois state line from her home in Missouri, where Republican lawmakers have made obtaining an abortion all but impossible. With a single clinic left within its borders and a seventy-two hour waiting period before an appointment can be scheduled, people in Missouri facing unintended pregnancies rely on places like the Hope Clinic for Women in Granite City, Illinois, where the bulk of the documentary’s action takes place.

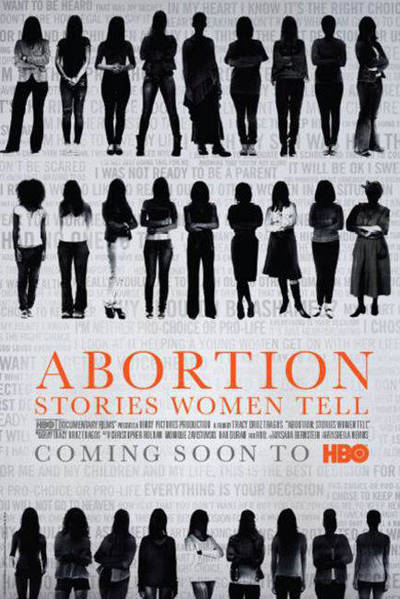

Though it’s located near St. Louis, Hope Clinic might as well be a world away for some of the patients who drive for hours for abortion care. And it is its own little world, a welcoming utopia for pregnant people like Ami, whose story is one of the main narrative threads woven through an intense ninety minutes of deeply personal, sometimes painful testimony. Producer and director Tracy Droz Tragos uses Ami’s story to introduce us to Hope Clinic and the women who run it: Chi-chi, the self-described “feisty” security officer who listens day in and day out to the ranting of protestors; Dr. Erin, the OB/GYN who performs abortions at the clinic and who is expecting her first child; Barb, a salt-of-the-earth, God-fearing nurse whose practical views of the world make a better argument for abortion than any politician could. They work with women of all ages, from different backgrounds, all of whom need abortions for different reasons.

Financial concerns are overwhelmingly cited as the impetus to abort. Ami herself works seventy to ninety hours a week just to make ends meet for her small family, while another woman explains that a having a fifth child on top of the financial burden of having two kids in college already would be impossible to afford. Some simply state that they’re not ready to have a baby, while another tearfully confesses, “My son’s father…he was gonna beat the baby out of me, anyways.” One couple turns to Hope Clinic with their pastor’s blessing after learning that their wanted baby couldn’t survive outside of the womb. A woman in a similar situation describes Missouri’s mandatory seventy-two hour waiting period as “heartbreaking.”

The title might suggest that all the women profiled will share stories about abortion, but this is at heart a pro-choice documentary, and all the choices are explored. From a seventeen-year-old who’s looking forward to the birth of her daughter despite the judgment of people in her neighborhood to a former drug addict who chose to give her baby up for adoption, Abortion doesn’t posit that termination is the “easy” way; it shows the viewer that no matter what the circumstance, there is no ideal solution to the problem of an unintended pregnancy. It also reveals how simplistic the thinking of the anti-abortion movement is with regards to adoption and parenthood without drawing attention or lending credence to those arguments. Instead, Tragos gives us a quiet moment with the couple who gave up their baby, illustrating the impact of their decision rather than explaining it to us.

Though the bulk of the film focuses on the women visiting and working at Hope Clinic, Tragos gives the anti-abortion crusaders their say, following a handful of them throughout the film without demonizing them. Sometimes, they demonize themselves, shouting “Be a man and don’t kill your baby!” at a crying couple as they enter the clinic or bringing their apple-cheeked children to sing “He’s Got The Whole World In His Hands” on the sidewalk outside. It’s hard to stomach anti-abortion crusader Susan Jaramillo as she talks candidly about the three abortions she had so that she could finish college and focus on her career (which now includes book deals and television appearances) when contrasted with Te’Aundra, a young mother who lost a basketball scholarship to Kentucky State due to an unintended pregnancy. In her small apartment, Te’Aundra rocks her baby and confesses that she regrets not having an abortion, and the viewer can’t help but remember Jaramillo’s sleek highlights and smiling face from her hardcover jacket as she endeavors to save young women from “automatic” shame and regret.

More frustrating are professional protestors like Anne, who saw her name in the center of the world “Planned” on a Planned Parenthood sign and interpreted it as a call from God, or the men who stand outside Hope Clinic every day, grinning as they hold up pictures of fetuses or engage in performative preaching on the sidewalks. They seem to delight in tormenting the patients and escorts as they walk in and out of the clinic, and enjoy hamming it up for the camera. Editors Christopher Roldan, Monique Zavistovski, and Dan Duran deserve a nod here; it’s often these precise, incidental moments more than direct interviews with the protestors that ram home how little concern or sensitivity the anti-abortion side has for pregnant people.

If I were to cite one complaint about the movie, it would be the lack of inclusivity in the language and overall concept of the film. Women aren’t the only people getting abortions, yet it’s still considered a “women’s issue” largely due to our heteronormative and cisnormative cultural perception. While it’s possible that no transgender men or nonbinary people agreed to be filmed for the documentary, the title itself is exclusionary; that none of the ninety-minute run time could have been sacrificed to even acknowledge the existence of these vulnerable people is disheartening and disappointing, and marrs an otherwise flawless take on reproductive justice.

This isn’t HBO’s first take on the subject of abortion. In 1996, their movie If These Walls Could Talk shocked cable audiences with haunting images of violence against doctors and the human cost of illegal abortion. Though that was twenty years ago, when Dr. Erin states firmly, “People will die,” it’s difficult not to be reminded of Demi Moore’s character bleeding to death on her kitchen floor. When a protestor stalks an escort to her car in Abortion, the grisly denouement of Walls‘s third act comes uncomfortably to mind. But while Walls was undeniably moving, the power of Abortion lies in its unadorned fact; during one segment, a fresh-faced young woman named Reagan admits that though she was shown graphic anti-abortion materials as a child, she’d never met anyone who’d had an abortion until she joined Students for Life of America, an anti-abortion organization. “I don’t have a personal experience with abortion,” she explains as she drives cheerfully to a college campus to recruit new members. It’s documentaries like this that aim to correct that disconnect, and that’s where Abortion truly excels. No one who watches this film could claim to have no personal experience by the time the credits roll. Abortion does too thorough a job making it personal while delivering a compelling film that’s impossible to walk away from unchanged.

Abortion: Stories Women Tell premieres Monday, April 3, at 8pm ET/PT on HBO.