One has to wonder why author Jennifer Weiner thought she was in a unique position to start a conversation about diversity in YA by creating the #ColorMyShelf hashtag on Twitter.

Natasha Carty, owner of the book blog Wicked Little Pixie, wondered: “Why is it a white author starting this hashtag? […] We need to talk about the issue, we truly we do, but some will always raise an eyebrow that it’s always the white author starting these types of conversations.”

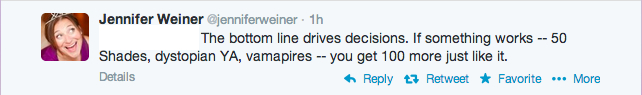

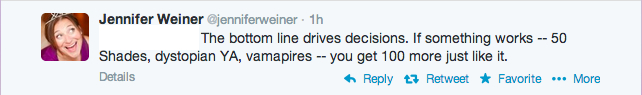

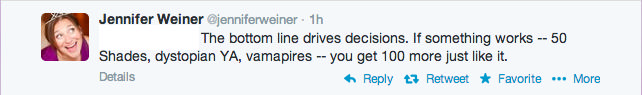

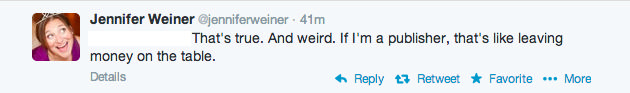

If this sounds unjustifiably cynical, consider the direction the conversation took when one Twitter user told Weiner that racism, rather than profit, drives the decisions of our predominately white publishing culture:

Is the publishing industry missing out on cash that could be earned by embracing diversity in their authors, offices, and readership? Of course they are. But Weiner’s inability to grasp anything but the bottom line underscores a commonly held position in the publishing world: that cultural diversity in fiction is only attractive if it is profitable and comfortable for white people.

The first title mentioned in #ColorMyShelf was Kathryn Stockett’s The Help, a novel in which a white protagonist gives voice to the oppression of black housekeepers. Asks Carty, “Who thought that The Help was a great book about people of color?”

It is unsurprising that it was a white woman making that particular recommendation. A book like The Help becomes a blockbuster because we white people care deeply about racism and social justice when we can be the heroes. We like to be reassured that we’re “not all bad” and that on a personal level, we couldn’t possibly be racist. We feel pity, rather than empathy, for the women of color on the page, and take pride in knowing that in this literary narrative, only we can heal racism through the power of our whiteness.

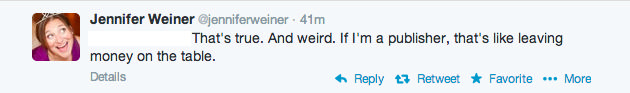

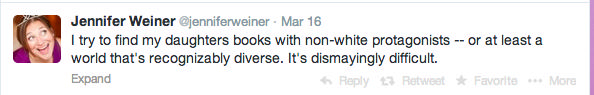

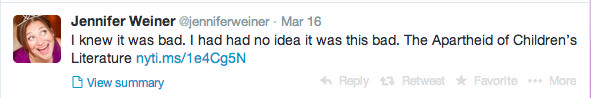

One can only assume it was this well-meaning sentiment– giving a voice to those who are underrepresented– that drove Weiner to start the tag in the first place. But as several twitter users pointed out, the conversation about the lack of diversity in fiction isn’t new. Weiner’s own crusade began after reading an opinion piece in the New York Times, “The Apartheid of Children’s Literature,” by author Christopher Myers. She took to Twitter to express her dismay:

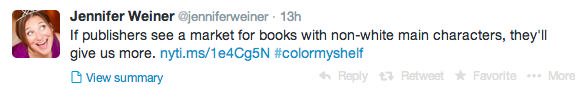

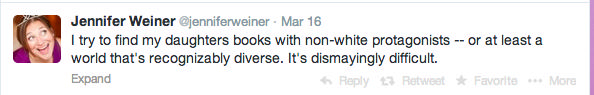

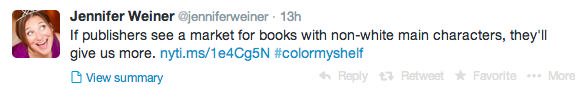

She bemoaned the difficulty she had trying to find non-white characters in her daughter’s reading material, and suggested a way to fix the problem:

But the issue at hand isn’t whether or not Weiner and other white mothers can find books to “color” their children’s shelves, nor was that the point of Myer’s article. Children of color deserve books that satisfy their need for representation, regardless of white interest and spending power; that Weiner wishes to purchase those same books for her daughter is and should remain a secondary effect.

Also troubling was the fact that many of the initial replies came from white women eager to boast the titles of the racially diverse books they’d given their children. As Carty states, “While the sentiment was probably in the right place, the amount of racism in the replies is disturbing.”

Considering the number of existing lists found by a simple Google search (including Melinda Lo’s “Diversity in YALSA’s Best Fiction for Young Adults“), it’s no wonder that Weiner’s leap from opinion piece to enlightenment was considered by some to be the actions of an “ally” using her platform to solicit education from the very people she believed she was helping. Rather than asking her followers to consider the predicament of non-white and interracial families trying to find fiction for their children, Weiner created a conversation directed by white need. How could we, as white readers, “color” our shelves?

That isn’t to say that valuable discussion didn’t come from Weiner’s hashtag, or that the venue was devoid of participation from authors, readers, and bloggers of color. Still, it was Weiner who created the hashtag and who began the conversation by suggesting that publishers should deliver more characters of color that white parents can feel good about and spend money on.

As white authors, bloggers, and readers, we must stop promoting diversity as a business opportunity or a chance to buy ally points with our disposable income. By perpetuating the white supremacist belief that all media must be created for white consumption and profit, we are erasing people of color from our literary legacy, no matter how good our intentions. Every child deserves to see themselves in stories they can enjoy, but it isn’t the place of white people to decide how and why those stories are created and marketed. If we truly seek diversity in fiction, we have to let the needs of others come before our need to define ourselves as social justice allies.

[In the interest of protecting twitter users from harassment, Weiner’s tweets have been photoshopped to remove user names.]